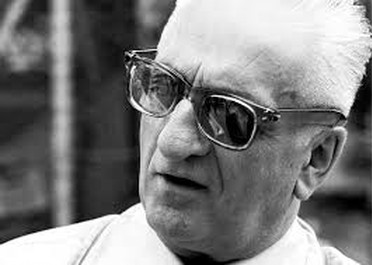

Enzo Ferrari, the Italian auto maestro, set his sight on the next Le Mans. It was the gathering turf of the world’s finest drivers, and the fastest cars. His legal machine was raring to go. But there was problem back home – his only child, Alfred, Dino for short, was bedridden, sick with a potentially terminal condition. Still, Ferrari was hopeful that things were going to pan out well and that his 24-year old son would be back up on his feet. Dino was diagnosed with muscular dystrophy in his teens and his skeletal muscles were slowly wasting away by the day. But he still had enough vigor to ask about his father’s latest car, which he always dubbed “the puppy.” The 625 LM was Ferrari’s latest build, designed to race at Le Mans, it had “Inline four-cylinder, 2.5 liter, two Weber carburetors…,” Ferrari told his son.

Visitor after visitor, Dino enjoyed the warmth of loved ones during this trying period. Among those was Jano, Italy’s foremost engineer who worked with Ferrari. The trio of Ferrari, Jano and Dino would eventually design a 1.5-litre racing engine that struck a perfect balance between power and economy of motion. The engine symbolized life, Enzo Ferrari felt, as he considered cars virtually animate creatures, breathing though carburetors and skinned with metal.

* * *

Having fought for so long, Dino died on June 30, 1956. Historians dissented regarding Dino’s disease, arguing conditions from leukemia to congenital syphilis, but the majority agree his death resulted from muscular dystrophy. What the condition was didn’t matter, though, to devastated Ferrari who noted from his last conversation with his dying son “what life means to a young man who is leaving it.”

The French Grand Prix was held the following day, and, wearing white armbands, the red Ferrari team blitzed to victory, setting the fastest ever speed recorded in European circuit history – 121.16 mph over 314.5 miles. Ferrari‘s loss was enough to quash any race triumph. He had little left in him for racing. At fifty-eight, Ferrari had to come to terms with the fact there was no legitimate heir to take over the legacy he had spent the greater part of his life building.

Ferrari’s curiosity for cars all began when he was 11. He’d hike two miles to watch Record del Miglio, a fledgling race competition organized by the Modena Automobile Association that assembled racers bidding to set a new mile speed record.

Ferrari’s racing dream was left in limbo following the ravages of World War I, which swept away his finances and left his father and brother dead. He was also not substantially educated, with three years of trade school his highest reach, but Ferrari had in him a priceless talent – fixing things. He would go on to join Alfa Romeo as a mechanic, test driver and competitor, winning his first race in 1923 at Ravenna. Ferrari founded private team Scuderia Ferrari in 1929 and won his last race in 1931. Jano was born the following January. Ferrari had Italy’s foremost mechanical genius Vittoria Jano, but he knew he needed a formidable match at the wheel to solidify Ferrari’s supremacy on the track.

Ferrari’s find? Tazio Nuvolari. Dubbed the “Flying Mantuan,” a practice drive once paired Ferrari and Nuvolari in the same car. Nuvolari’s near-superhuman abilities were brought before Ferrari’s very own eyes, who recalled that “At the first bend, I had the clear sensation that we would end up in a ditch; I felt myself stiffen as I waited for the crunch. Instead, we found ourselves on the next straight with the car in a perfect position. I looked at Nuvolari. His rugged face was calm, just as it always was, and certainly not the face of someone who had just escaped a hair-raising turn. I had the same sensation in the second bend. By the fourth or fifth bend, I began to understand. I had noticed that through the entire bend Tazio did not lift his foot from the accelerator, and that, in fact, it was flat on the floor.” Tazio Nuvolari and Vittoria Jano were the perfect tag team Ferrari needed to power his Scuderia Ferrari team to the pinnacle of glory in the history books of Italian racing.