In Modena, Surtees was a top favorite. The world champion attracted locals and signed autographs as he walked the streets. However, as the 1965 season gained momentum, tension grew at the Ferrari factory. From broken engines to bent metal, Surtees suffered a turbulent start to the season. To compound his woes, team manager Dragoni was not on his side, the latter preferring his Italian compatriot Lorenzo Bandini as Ferrari’s number one driver. Surtees felt the Formula One team’s poor performance wasn’t about him but the fierce rivalry with the Americans. For Ferrari, it was all about his sports cars. There was little attention on the F1 campaign, a move that didn’t go down well with Surtees.

Before his clash with the Americans at Le Mans, the 12hrs of Sebring was a good test to see how his cars fared against his American opponents. Ferrari was aware Henry II had made huge financial decisions getting his Ford ready for Le Mans. He wasn’t going to allow any hothead from Dearborn to dethrone him as King. Beating them was top priority. At his factory, the team was busy making arrangements for the journey across the Atlantic. Sebring was another racing competition Ferrari dominated. But heading into the 1965 duel, he heard a rumor, one that truncated his plans. It was about the Chapparral, a car built by Jim Hall. The Chapparral was by no means legal for the race, it had no trunk space and weighed less than FIA requirements. However, it was one of the fastest racing cars around. Ferrari didn’t want to be embarrassed by a car that flouted official regulations. He opted out.

And it turned out the Moranello boss was right, no car could match the Chapparal in speed. Right out of the gate in the opening laps, the Chaparral took an unassailable lead. Torrential rain came halfway through the race, slowing things down and making visibility difficult. Phil Hill took his Ford GT40 into the pit, and as soon as he’d open the door, water came pouring out. Punching the floorboard to drain the water, a mechanic came to his rescue. The race continued. Meanwhile, in the paddock, Shelby’s truck driver Red Pierce was spotted unconscious, he’d been electrocuted by a soaked generator. The race was anything but successful. By the time the race ended, four drivers, two spectators, and one truck driver were nursing wounds in a nearby hospital. There was little Shelby’s cars could do to stop Jim Hall’s Chaparral, the latter stealing the show in a comfortable win. Ferrari was dethroned at Sebring. Although Ford racers Ken Miles and Bruce McLaren were given the prototype-class trophy, Media rave was all about the Chapparal.

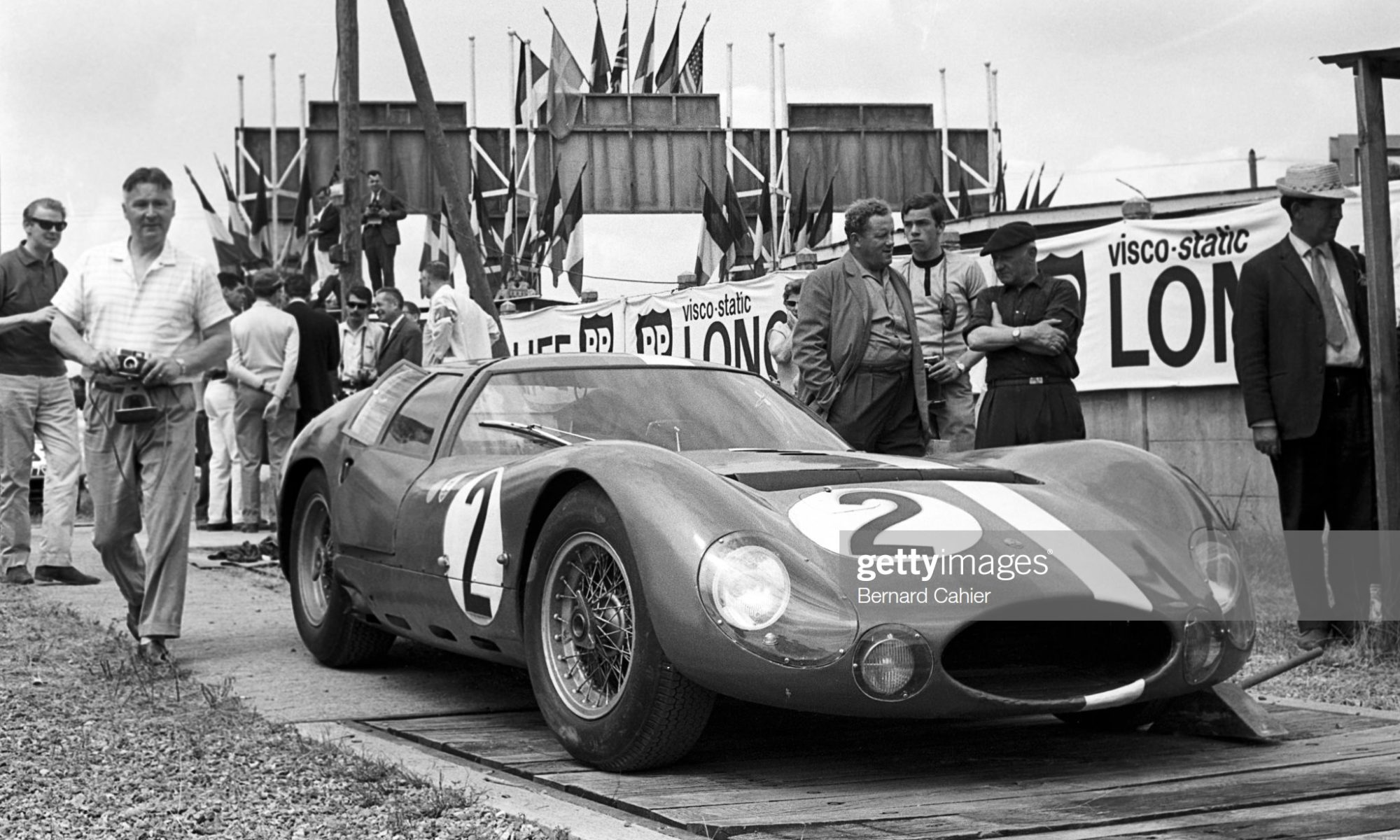

The Le Mans test weekend was next. And John Surtees continued from where he stopped the previous year, setting a new lap record in Ferrari’s newest build – the 330P2. The Inter-Europa Cup 1,000 Kilometers at Monza and the Nürburgring 1,000 Kilometers in Germany followed. Ferraris were winning across the board. The Ford/Ferrari duel ahead was the talk of the media.

Don Frey’s secretary informed him that Roy Lunn was on the phone. He was calling from his shop Kar Kraft, where he’d spent most of his days working on Ford’s next-generation cars for Le Mans.

“I got something I’d like to show you,” Lunn said.

“Do you want me to come over there or can you bring it here?” Frey asked.

“I’d rather you came over. You’ve never seen what we’re doing down here.”

On his arrival, Frey took a tour of the facility at Kar Kraft. While the GT40s were in Shelby’s hands, Lunn and his team of technicians, draftsmen, and secretary where busy building the new prototype for Le Mans.