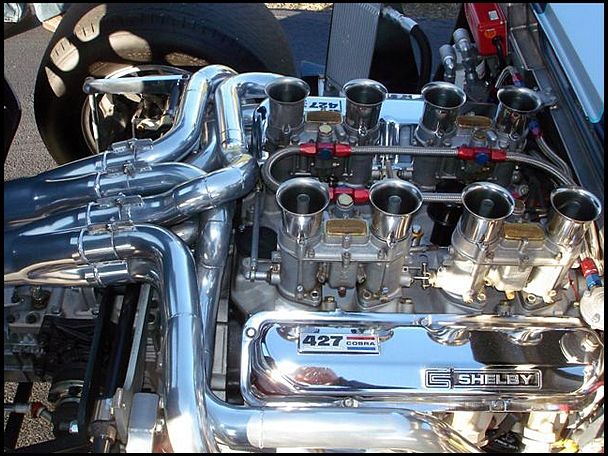

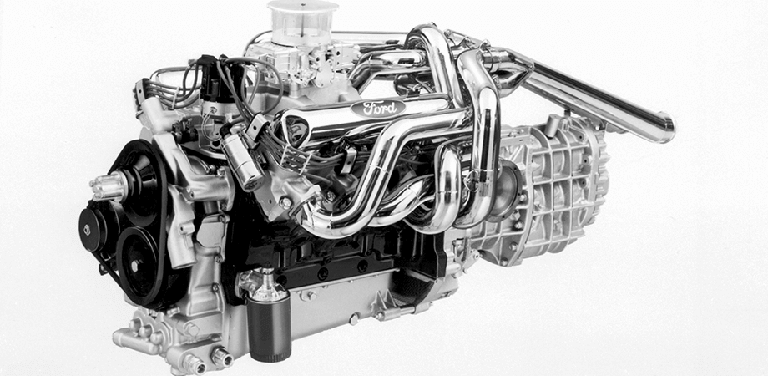

The new car had a massive 427-cubic-inch V8 mounted behind the cockpit. It was the biggest engine Ford had ever tucked into a production car. Lunn explained what the car was all about and the modifications they made. The engine was equipped with high-compression cylinder heads, a special high-rpm camshaft, and aluminium intake manifolds. The seating position was brought forward, and the front end was redesigned; the nose was longer, with a gentler slope and blade-like sharpness, unlike the one in Shelby’s design. Frey was impressed. It was May, and Le Mans was only a month away. Up until then, both men never thought they’d be able to build a formidable prototype for the 24hr race.

They had to put the car to the test though. Lunn got a test driver named Tom Payne for the task. The drive on Ford’s Dearborn track impressed Payne. So Lunn moved things further. They’d see how the car performed on a high-speed test track in Romeo, Michigan. Ken Miles and Phil Remington made the trip from Los Angeles. There was also Tom Payne. Payne was first to put the car to the test, clocking a personal-best lap speed of 180mph. Miles was next. He was more experienced than Payne. Lap after lap, adjustments were made. Rocketing his way down the straight and past the crew, Miles hit a 201.5 mph lap speed, and 210mph on the straights – more than tripling Michigan’s speed limit.

Done with test day, the team headed to a hotel for a debriefing. “What does everybody think?” Lunn asked. “That’s the car I want to drive at Le Mans this year,” Miles replied. The new build was dubbed Ford Mk II, and an agreement was reached to have two of the 427-cubic-inch engine cars ready in time for the 24hr duel – now a fortnight away.

One morning, a week before the team departed for Le Mans, the Deuce and the entire Board of Directors visited Shelby. The Glass House Boss was in good mood, everything seemed to be falling into place ahead of the clash with Ferrari. It was only days earlier that “The Flying Scot” Jimmy Clark won the Indianapolis 500 in a Lotus-Ford, leading the pack in 190 of 200 laps and brushing aside A. J. Foyt’s record with an average of 150.686 mph. Sealing the big one at Le Mans was all that was left, and this was Shelby’s task.

Meanwhile, the Ferrari team was also making its final preparations for the showpiece. The team headed to Monza. The mission was to replicate all conditions synonymous with the 24hr race. Surtees was on hand as usual, as was Bruno Deserti – a new recruit. Team manager had brought Deserti in for a trial. Surtees drove off in the 330P2. Lap after lap, it was another easy day for the champion. Deserti was hoping to win Ferrari’s heart, to achieve his dream of racing a Ferrari on the big stage. He had to prove himself, and there couldn’t be a better chance. Taking his turn at the wheel, Deserti slipped on his white helmet and zoomed off, lapping comfortably at 1:58, then 1:52, then 1:50. Surtees’ record time on the day was 1:32. Then there was silence, the red car was out of sight. Only Lorenzo Bandini saw what happened, Deserti had veered off the track into the woods.

“He’s out!” Bandini screamed. “Let’s go! Let’s go!” The car was found 50 meters into the woods. Wrecked. Inside was Deserti, the young man’s dream to become a Ferrari racer came to an end disastrously. He struggled but lost the fight for his life, dying a few minutes after 7:00 P.M. The test day was anything but successful. The 330P2 was fast, no doubt. But would it survive 24hrs? The gearbox, suspension, and engine? With race day only days away, there was enough time to address these concerns. The Ferrari team was left with critical questions unanswered heading into the 1965 Le Mans.