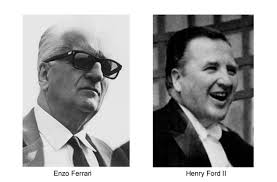

Taking his turn to deliver the delivering the keynote speech of the annual meeting of the Society of Automotive Engineers, Henry II raised concerns about America’s position in the racing world.

“This is a year like other years in which America will arrive at a series of crossroads in the long journey in search of our national destiny,” he began. “For generations our technology has been the most advanced and progressive in the world. It is the basis of our standard of living, of our national security, of our position in the community of nations. We have grown accustomed to thinking of ourselves as the unchallenged masters of the machine age.”

“Fifteen years ago, such self-confidence was fully justified. The rest of the world came here to learn how to make things better and cheaper and faster. More recently, in industry after industry, we have seen new processes developed abroad and then adopted here. We have seen foreign products challenging our own, even in our domestic market, not only because the foreign products are cheaper but also because they are often better and more advanced. Signs such as these suggest that we should be asking ourselves some important questions.

“Do we still have more to teach the world than it has to teach us?”

Thousands of miles away, in Slough, London, Ford was about to have a prototype Le Mans car ready for the big stage. The task involved a gathering of the best brains, led by Roy Lunn in the engineering department.

There was also Carroll Shelby and John Wyer in the mix. Wyer, Shelby’s former boss at Aston Martin, had joined Ford in 1963 in an offer that more than doubled his earnings at Aston Martin. Iacocca’s number two, Don Frey, went scouting for an engineering consultant. His search would bring in ex-architect Eric Broadley into the team. Broadley founded Lola, a racing company that raced at Le Mans with a Ford-type prototype. He was more likely to think the Ford way and had access to suppliers the team needed. He joined on a two-year contract. Shelby’s chief engineer Phil Remington completed Ford’s army of experts.

Le Mans was fast approaching – some 250 days away from Ford’s showdown with Ferrari. It was 12 hour workdays at Slough. No weekends and holidays. The car in the making was one with frightening speed and durability on the race track. Getting all parts in America was difficult, and so Lunn embarked on a European tour cashing in on the most sophisticated components available. Girling brake calipers and metalastic driveshaft couplings were available in England, Borrani fifteen-inch wire-spoked wheels and Colotti transaxles came from Italy, and other parts were supplied by Dearborn engineering laboratories.

Comments from Paul… Roy Lunn, the father of the GT40… we all owe him a lot!