In 1963, one year after Henry Ford II pulled out of Detroit’s Safety Resolution, race drivers took to the tracks brandishing trails of speedy Ford cars. With the economy turning the green light, thirst for cars went up north, almost crushing the 1955 sales record. It was busy days at the showroom, driven by Ford’s glory and Shelby’s “Powered-by-Ford” Cobras.

The New York Times officially put Ford’s soaring sales on the front page “Does winning automobile races sell cars?” and “You bet it does,” the article began. It was obvious success on the race track was an assuredly powerful marketing instrument with “immediate and remarkable” upsides, the article noted.

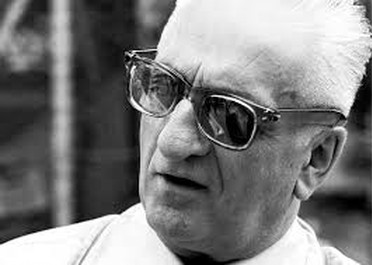

Noticeably away from the Glass House, the Deuce began his next big quest. He was off to London, aiming to drive his company to even greater heights away from home turf. Asked about his trip to Dagenham – the Ford factory location and Europe’s biggest industrial metropolis, the Deuce responded: “I came to Europe to see what was becoming of our investments, which between 1960 and 1964 will have totaled $800 million.”

Henry knew what happened in the United States was finding its way to Europe – a rise of the middle class and everything it brought to the economy. While the company churned out 1200 Ford Cortinas daily, the Deuce was sure that was far from the number needed to match the surging demand in a continent whose economy was beginning to thrive following the plummeting effects of World War II.

His sights on Europe, Henry II embarked on his ambitious project, the scale of which was unprecedented in the history of the Ford empire. Getting started, the company got a new plant operational in Halewood in the UK, employing eleven thousand workers. And near Dagenham, a foundry was in the offing, with a huge power station enough to accommodate the electricity demands of a city numbering 160,000 population. The Deuce’s inkling for Europe wasn’t unexpected though, given his father’s adoration for the continent until his death.

Edsel saw in Europe a world full of opportunity, fantasy and beauty all through his life.

Ford cars were arguably the best in the world, but away from that, Henry II had more to his marriage to Europe – a woman. He’d met thirty-six-year old- Cristina Vettore Austin in Paris. But this was an illegal affair, as he already had three kids in a twenty-one-year-old marriage. His interests began to waver between Dearborn and Europe. The team at Glass House knew there was something wrong.

Success in Europe was critical for Henry II. He would have left a legacy behind if things panned out well. However, as media outfits soon uncovered his adventure, Ford’s fortunes in Europe looked anything but bright. It was unbefitting of a man steering the affairs of the world’s second-largest company to be embroiled in infidelity. Left unattended, the collision between business and personal life was simply a matter of time. This was clear to Henry II. “He was like a time bomb,” “You could almost hear the ticking,” a ford executive later recalled.